By Dr. David Paddock, Guest Writer

By Dr. David Paddock, Guest Writer

We are in the midst of a sea change when it comes to financing medical education. I'm, of course, referring to the Saving for a Valuable Education plan (SAVE) implemented by the Department of Education in 2023. This is the latest income-driven repayment plan with more advantageous terms and, critically, an interest subsidy when the loans enter repayment. It also qualifies for the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program (PSLF), which eliminates remaining debt after 10 years of working with a nonprofit organization.

Pursuing a career in medicine is an extreme exercise in delayed gratification—not just for us, but also for our families and friends. In the process of researching and writing this guest post, a friend and fellow fourth-year medical student passed away under unexpected and tragic circumstances. At 32 years old, he had worked most of his adult life to pursue his dream of becoming a physician. Wealth is not just accumulation but freedom and flexibility to better dictate certain areas of our lives. Unfortunately, some don't get the chance to exercise that freedom . . . with terrible fallout for their loved ones.

The story below is a personal one with a unique set of financial and professional circumstances. The analysis you'll eventually see makes a lot of assumptions that are quite simplified. Many of the conclusions run counter to the traditional views you'll see here on The White Coat Investor. My goal is to help medical students consider the following question: is it safe, wise, and effective to invest during medical school, and is there a reasonable case for debt?

Disclaimer: I am not a financial professional. I am just barely out of medical school.

Life Before Medicine

I'm a non-traditional student. For about 10 years, I worked a plethora of healthcare-adjacent jobs—from paramedic to EEG technologist, none of which paid particularly well. I lived in the metro Washington DC region with a high cost of living, and I soon began racking up credit card debt. Not a great start. In typical millennial fashion, I started picking up additional work to pay the bills and save a bit, eventually incorporating an LLC as a sort of "catch-all" for any 1099 work I picked up on the side. This varied tremendously from phlebotomy at sleep labs to one-off CPR classes, eventually growing as offers for bigger projects started rolling in. At its peak, I was earning an additional $1,000-$2,000 a month working part-time gigs, mostly teaching ACLS and PALS.

At 27 years old, I decided I wanted more out of my career, and in 2016, I began preparing for medical school. This was an intense decision but not the focus of this piece. I enrolled in a night-class certificate program for career-changers at my local university. The idea of a special masters was initially appealing, but these tend to be expensive and full-time—I could afford neither.

The job market started to improve, and I landed a full-time gig as a program manager, which afforded me a bit more financial flexibility and time. The part-time work relaxed as the college classes took priority. When COVID hit, demand collapsed, and I got a terrible deal on a PPP loan (as did many other independent contractors), thanks to the formula used to calculate net earnings for independent contractors. This was eventually revised to a calculation based on gross earnings, but past recipients were unable to reapply. My full-time employer was gracious enough to let me "spend down" my PTO bank, pushing out my termination date and extending my health insurance coverage until the university's kicked in. I entered medical school in late 2020 with an emergency fund of about $10,000 and about $7,000 in a handful of pre-tax retirement accounts, having worked my way back from $20,000 in credit card debt and no savings about five years prior.

You'll notice the path above was, shall we say, time-intensive. I spent the entirety of my 20s working 50-60 hours per week almost every week. Friendships faltered amid full-time work, part-time gigs, and nighttime classes. It was an intense and lonely experience that I have no intention of ever repeating. Mending those relationships is an ongoing process, one I try to prioritize as much as possible.

More information here:

The Role of Student Loan Refinancing in 2024

Capitalizing on SAVE: Loan Repayment Strategies for Students and Residents

Working in Medical School

To my surprise, most medical schools strongly discourage working. Some outright prohibit the practice. I'd spent the preceding decade hustling to build a business and earn income, so much so that it seemed irresponsible to set it aside completely. It occurred to me that any income I earned could easily be set aside and invested as I went, leaving the loans for living expenses. After some careful thought, I decided to work as much as I could throughout medical school as long as it didn't interfere with my performance, especially over the first two years. After explaining my situation and goals, I found support from an associate dean, who approved my plan and even offered a couple of days of "flex time" to work on larger projects.

Once I got the green light, I started reaching out to old clients in my spare moments between flashcards, lectures, and exams. I even traveled back to old employers between preclinical blocks, mostly to teach ACLS and PALS for a couple of days in a row. I also added tutoring to my repertoire—which felt like a natural extension of teaching—and built a profile on a tutor-matching website to attract new clients. Eventually, I was working with 3-4 students at a given time, most of whom were studying for the MCAT, and engaging in a larger consulting project, usually facilitating some kind of training, once or twice per quarter. On average, this provided about $1,000 per month—enough to meet my savings goal, cover taxes, and provide a little extra fun money.

Student Loans and IDR

Before taking the plunge, I attempted an amateur analysis of various funding mechanisms for medical school. I strongly considered the Health Professions Scholarship Program (HPSP), but because I was almost completely undifferentiated on a specialty, I decided this wasn't the best option. The consolidation of military medicine into the Defense Health Agency was in the early(ish) stages around this time, which also introduced some uncertainty. With HPSP excluded, I wanted to compare spending down savings (to minimize loan burden) vs. borrowing for the entirety of medical school and continuing to save and invest.

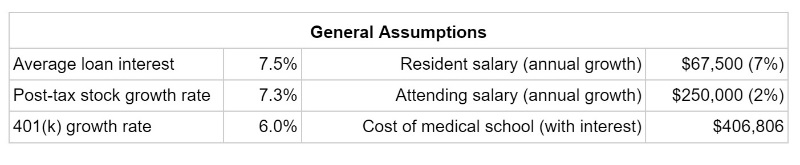

To complete the analysis and make it more applicable to other students, I added an additional category, compared three paths, and projected their savings and loan burden for an additional 20 years after medical school. This final category was a student who received financial support from their family. This analysis also assumes identical residency and attending salaries and participation in income-driven repayment plans, specifically the SAVE plan, which limits interest capitalization during residency. I compared three paths using the parameters below:

Student A: Parents or family pay 50% of medical school tuition

This was, by far, the best option for the student. It essentially equates to a subsidized cost of attendance, but the benefits are less than one might expect. The student carries less capitalized interest from the student loan over the four years of medical school. However, the latest generation of income-driven repayment plans has created a payment ceiling for the entire duration of residency while limiting interest accrual. I discuss this more below, but essentially, this student's family sacrifices retirement security for the student's lower principal and fails to account for subsidies or repayment benefits.

Student B: Spending down $100,000 in previous capital to avoid loans; then funding with loans

I personally know a couple of fellow non-traditional colleagues who took this approach. The most common path involved converting home equity into cash for medical school tuition and living expenses (selling your house to pay for training). This approach lowers the total cost of attendance by $100,000, but it also sacrifices the 6%-8% compounding return that $100,000 could net in the long run, which is significant. Again, with the subsidies being offered in the federal student loan programs now, this ends up being a huge step backward in financial security and involves a huge personal opportunity cost.

Student C: Funding entirely with loans while earning $10,000 per year in side-gig money

This student has the highest loan burden overall, but because those loans benefit from income-driven payments and interest capitalization subsidies, the cost during residency is essentially the same, especially if borrowers take advantage of forgiveness programs like PSLF. It's not feasible for everyone to work during medical school, and it is likely based on their ability to generate a higher-than-average hourly wage using skills from a previous career. But the benefits are very real: four years with minimal income and near zero tax liability to build a financial base for residency and convert retirement to post-tax accounts. Bias alert: this is what I did, so my analysis is likely tilted in favor of this path.

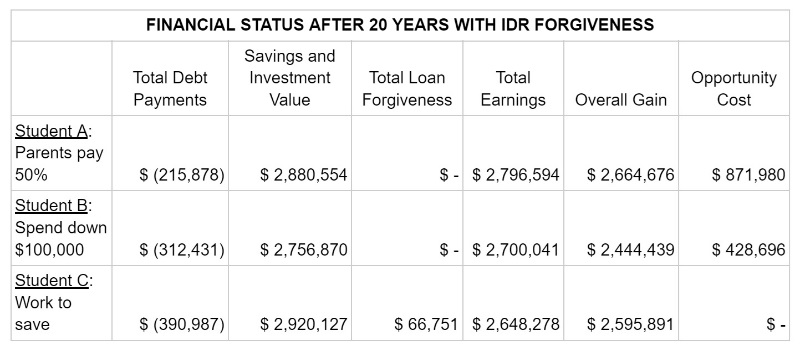

Here are the results:

To quickly summarize, this analysis assumes all residency and attending salaries will be modest for a physician at $250,000, held the same across for the three students. The personal contributions for Students A and B are added back as front-loaded subsidies as if the student will rely on those funds until they're exhausted and then take out loans. It also assumes an aggressive savings rate after residency, utilizing all available pre- and post-tax vehicles while limiting post-tax spending to $120,000 per year as an attending. Check out the general assumptions box above for more details.

Over the 20-year horizon, only Student C takes advantage of IDR-driven forgiveness. PSLF-driven forgiveness benefits Students B and C more significantly (see below). Despite taking out more loans than Student B, Student C actually ends up in a better financial situation after 20 years because of their additional time in the market. Student A remains the obvious winner but at a massive opportunity cost to their family. Student B's opportunity cost is also quite high, as that initial $100,000 sacrifice would have grown substantially if invested. All of this is thanks to the subsidies built into the SAVE income-driven repayment plan, which caps payments at a fixed percentage of income and prevents interest capitalization as long as payments are being made.

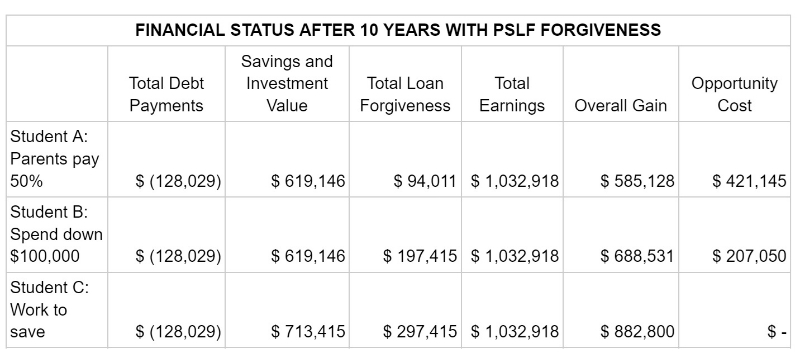

Now, let's add PSLF into the mix.

Qualifying for PSLF is even more beneficial to those with high debt burdens. At this stage, total earnings and total debt payments are identical since all paths get their loans forgiven. Student C, however, gets an early lead on savings and investment value, thanks to the nest egg they built during medical school. Had Students A and B invested their cash instead, they would undoubtedly be further along.

More information here:

4 Pillars for High-Income Families Paying for College

Discussing Financial Sacrifice

While researching and editing this piece, I noticed there was a cutoff point where a higher income made electing an IDR plan no longer worthwhile. I estimate it falls somewhere between a $250,000-$300,000 annual salary, and sure enough, WCI's recommended financial advisors generally recommend against IDR plans if one's debt-to-income ratio is less than 2. Based on my chosen specialty (which I've purposefully elected not to disclose), I anticipate a ratio of about 1. So, why am I bucking the sage advice of the illustrious WCI?

For me, it all comes down to personal circumstances. I agree that, at a certain point, the recommendation to "live like a resident," avoid IDR, and prioritize paying off debt makes financial sense. It also requires a higher degree of delayed gratification—and not just from me, but from the people in my life. Personally, I feel little reason to inflate my lifestyle beyond a pretax income of $80,000, which is the most I've ever earned in my life. I'd rather have time—time with family, friends, and hobbies, and I'm willing to buy back that time with an IDR plan's higher long-term sticker price. But electing to save and invest along the way, especially developing a nest egg during medical school, offsets quite a bit of this cost.

The elephant in the room is uncertainty surrounding repayment options, specifically whether the SAVE plan will survive in this political climate. I have limited experience here, and I will simply say this is a risk I can tolerate. The trajectory of loan repayment options has favored graduates more heavily over the last 20 years despite the political discourse. Even if this changes, physicians qualify for some of the most generous repayment programs available, which can be leveraged depending on your willingness to work in certain areas and with certain groups.

Picking a Strategy and Setting a Goal

My investing strategy will surprise no one who reads WCI: Low-cost index funds. I have a handful of funds that track major indices, a REIT ETF, and several specific funds with additional growth stock exposure. My average expense ratio is 0.11% which I've been working on getting lower. I've experimented a bit with equal-weight indexed and dividend-producing ETFs. I briefly tried picking stocks, and I was met with a tidy loss. There was also a $1,000 foray into cryptocurrency that lost half its value but made for some nice tax-loss harvesting.

More information here:

We Quit Paying Extra on Our Student Loans (and Why It Feels Dangerous)

Should You Pay Off Debt or Invest?

The Thesis, the Outcome, and the Future

My argument is simple: The SAVE plan has changed the calculation for young physicians. By preventing interest capitalization over the course of residency, physicians in training can be less concerned about ballooning loan principles and can instead focus on saving for the future. For some, that may mean working even longer hours, stashing their money away, and rapidly accumulating a nest egg. For others, it may mean dialing back and prioritizing other areas of their life.

In truth, the financial outcomes between the three paths differ little over the long term. Financial behavior after residency matters far more, something this blog has covered well. I believe there are wrong answers, like sacrificing your family's financial security for your medical education (read: letting your parents pay for medical school), especially now that the SAVE plan provides the benefits discussed above.

I'll go even further: if the plan survives a legal challenge, there is a strong argument for financing medical education with federal student loans regardless of your financial situation. You may find, as I did, that saving and investing in medical school can offset some of the delayed gratification (financial and personal) that comes with this career, enabling you to get back to the areas of your life you may have been neglecting for the past decade or so.

From a financial perspective, I'm happy to report that I achieved my financial goal with just over $70,000 invested. My portfolio grew at a modest 8% per year despite the rollercoaster from 2021 to 2022. My contributions were preferentially distributed into a Roth IRA and a standard brokerage account, with total earnings during medical school of just over $44,000.

I want to explicitly give a nod to those physicians who came before me, especially the readers and contributors to WCI: thank you for paving the way for better debt management through advocacy and education. While I don't believe all undergraduate and graduate education should be interest-free, medical school absolutely should. My generation needs to continue advocating for the next generation of physicians—our field and our patients deserve it.

[Editor's Note from Student Loan Advice's Andrew Paulson: Regarding his statement, "There is a strong argument for financing medical education with federal student loans regardless of financial situation and investing existing savings," I know WCI Founder Dr. Jim Dahle feels quite differently about this. He and I generally feel that if you have enough money to pay all or most of your student loans upfront, you're better off not borrowing your loans at all and cash-flowing as much of it as you go. If you don't have enough to make a significant dent, you should borrow. But do it responsibly and don't take out more than you need. There is quite a bit of moral hazard in here, though, because now the federal loan system encourages you to max out borrowing. At the end of the day, you could get it all forgiven with PSLF. But not everyone who goes to medical school will work in public service. Not everyone in medicine is going to work full-time after training. PSLF is not a one-size-fits-all solution. But the current system encourages you to borrow more than you should because you could end up paying pennies on the dollar via PSLF.]

Do you think it's better to take out student loans so you can invest the money you already have? Why or why not? Is there a better way to pay for medical school? Comment below!

[Editor's Note: Dr. David Paddock is a graduate of Rush Medical College in Chicago and a founding partner of Outpatient Solutions LLC, a small consulting group that provides learning and development services to hospital systems, research organizations, and for-profit businesses across the country. This article was submitted and approved according to our Guest Post Policy. We have no financial relationship.]

The post How I Financed Medical School After a Late Start (and How SAVE Changed Everything) appeared first on The White Coat Investor - Investing & Personal Finance for Doctors.

Be sure to Refinance Your Student Loans, sign-up for our Online Courses, and listen to the WCI Podcast!

Unsubscribe from these daily financial articles

Manage all your subscriptions

If you NEVER want ANY emails from us again, you can unsubscribe from EVERYTHING | Update your email address by clicking here

White Coat Investor | P.O. Box 520421, Salt Lake City, Utah 84152

No comments:

Post a Comment

Keep a civil tongue.