[Editor's Note: WCI is so excited to present a pair of new courses in the Fire Your Financial Advisor series: FYFA For Students and FYFA For Residents. And since we're so proud of all this great new info, we're offering a special deal. From now until June 7, you can save 20% off any FYFA course by using the code LAUNCH20. For the student course, you'll begin learning the foundation of your financial education, including the math of doctoring and how to deal with student loans; the resident course will refine that education with discussions on how to become financially literate and why insurance is so important. The truth is you can't afford to wait to learn about finances. So, take the next (or first!) step now by exploring the new FYFA courses. And save some money while doing so!]

By Dr. Neill Slater, Guest Writer

By Dr. Neill Slater, Guest Writer

I never thought I would become a victim of financial fraud. I guess no one does. I've been a partner in an ER physician group for 15 years. I'm well-versed in personal finance and naturally skeptical, and I think of myself as an astute judge of character. I own several businesses, and I have extensively invested in residential and commercial real estate. I even have a non-medical MBA. Yet, I was conned like anyone else.

What I'm about to tell you is embarrassing. I accept that failure is a part of business and life. However, trying and failing is emotionally different from being duped, so this is one story I've kept to myself for years. I'm only telling it now because of recent developments and so others may learn from my errors. This is the story of how I got scammed out of $75,000 by a smooth-talking dentist.

Financial Fraud

If you search online for "doctors and fraud," you will get a list of articles about physicians committing crimes. Even when you Google "doctors being victims of fraud in the USA," you get results discussing Medicare fraud and other scams perpetrated by physicians. One of the only articles I could find concerning doctors as victims was from MedicalEconomics.com in 2016, titled 6 Reasons Doctors Get Scammed, by someone named Dr. Jim Dahle. Perhaps you've heard of him. You would be mistaken if this lack of media attention makes you think doctors and other medical professionals are not susceptible to fraud.

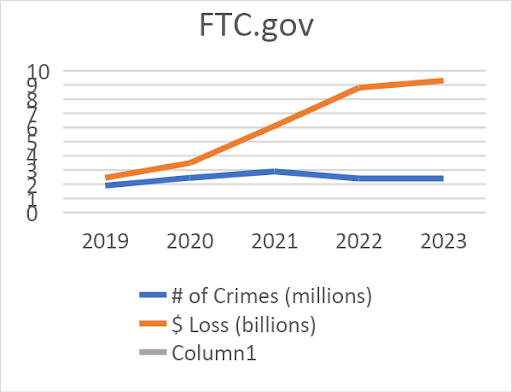

Approximately 2.4 million cases of financial fraud are committed in the US each year, causing billions of dollars in losses. While fraud cases have remained relatively constant, the economic losses have steadily increased. Financial fraud can be broken down into seven categories: products and services, charity, phantom debt, prize and grant, relationship and trust, employment, and investment. Criminals target different populations for each type of fraud, with physicians most often falling victim to investment fraud.

More information here:

Beware of Pump-and-Dump Schemes

The Encounter

I met "Trent" at an outdoor bar with my friend and business partner "Barry" in late 2017. It was one of those beautiful winter days in Austin, where you can enjoy being outside. Barry informed me that Trent's dental business was a few steps ahead of our urgent care company, and he thought we could learn something about growth from the meeting. While we sat under a heat lamp and enjoyed a beer, Trent told us his story.

He graduated from dental school in San Antonio and then moved to Dallas, where he started a dental office. He got married, had kids, and focused on his business. In time, he learned about marketing, billing, and how to run a profitable dental practice. Like doctors, he told me that most dentists are bad at business because they are never taught in school. Once he figured things out, he rebranded to a slick, new dental format and brought on investors, which allowed him to expand rapidly and hire other dentists to work for him. After a few years, he had 11 profitable locations. He admitted that he let the success and money go to his head, and he was caught cheating on his wife. The resulting divorce forced him to sell his ownership of the business. He waited two years for his non-compete to end, and now he was back, doing things right this time. He had already raised money and had started a few dental offices in Austin, and he was looking to expand.

Trent was handsome, charismatic, and relatable. He came across as humbled by his divorce yet confident in his knowledge of the dentistry business. We discussed the similarities between the urgent care clinics that Barry and I owned and what Trent was doing. Trent did not ask me for any money, and I left feeling he was someone with whom I could be friends. He clearly knew marketing and branding. I had seen his offices and advertisements around town, and they were fresh, slick, and new—seemingly the perfect fit for Austin in 2017.

The Investments

Barry and a few friends had already invested in one of Trent's dental clinics in a trendy Austin shopping district earlier that year. I was invited to join the LLC they were forming but passed on it, simply because I had several projects going on at the time and didn't have enough bandwidth to deal with it. The investment had gone well, and they had already received some profit distributions. A few weeks after the meeting with Trent, one of Barry's friends got engaged and needed to sell a portion of his investment in the dental office to help fund a lavish wedding. He asked if I wanted to buy out $25,000 of his stake. Since I knew the other participants and it was already profitable, I agreed and became an investor in my first dental office.

In February 2018, Trent learned about my investment and emailed me about a new clinic he was opening in an up-and-coming location. He told me he was buying an existing practice to rebrand and implement his operating system. I was already familiar with the dental office he was buying since it was close to where I lived. I had previously reviewed his offering documents the year before and had seen P&L statements from the other clinics, so I didn't ask for any further information. After a few conversations, I received a contract by email, and in late February, I wired him $50,000.

Who Falls for Financial Fraud?

Why would I invest $75,000 with someone I hardly knew? Investing in private companies is not uncommon for medical professionals. An ER colleague of mine made a $1 million return on a mosquito spraying company in Florida. I know a CT surgeon who made a bundle in hotels. But just like stock returns, these examples demonstrate survivorship bias. We've all heard colleagues hyping their early investment in Apple or Tesla but rarely hear anyone discuss their losses in Enron or FTX. Similarly, doctors aren't typically bragging in the lounge about the loss they took on an oil drilling venture or the pizza chain that went to zero. However, I understood the risk of investing in private companies, and I was aware of the existence of fraud.

So, what was it about me that made me susceptible?

Demographic and psychographic research on fraud victims is inconsistent at best. This may be due to the low reporting rates by victims or the fact that scams are continuously evolving. Some reports suggest higher levels of education and higher degrees of financial risk-taking lead to increased rates of fraud victimization.

While the data may be mixed, it is clear that doctors and other medical professionals make enticing victims. The six reasons outlined by Dr. Dahle in his article give us further insight. Doctors have no formal business or finance training despite our many years in school. Doctors are busy, and they tend to be overconfident and have an outsized trust of professionals. They also suddenly become accredited investors despite lacking experience. This combination of factors leads to physicians being a target for scams, particularly investment fraud. Looking in the WCI mirror, four of the six applied to me.

More information here:

Can You Spot the Unbelievably Bad Financial Advice on These TikToks and Tweets?

The Realization

It didn't take long for me to realize my mistake. By late May 2018, there was already a feeling that something wasn't right. Communications from Trent had slowed or ceased, and financial information was being withheld. Our investment group emailed Trent to request a meeting. He promptly replied, agreeing to talk the following Monday. That was the last time I ever heard from him.

In August, a lawsuit was filed against Trent by another group. He was allegedly selling the same interests to multiple investors. This filing reported that the south Austin location I invested in was a complete sham, as there was no agreement to purchase the existing practice. Our group had invested a total of $550,000 with Trent. All but one of us were physicians.

The Fallout

Only 14% of financial crimes are reported to the police. If it were up to me, I wouldn't have said anything to anyone except my accountant. I understand why victims are hesitant. There is embarrassment and shame when you realize you've been defrauded. I still feel ridiculous knowing that I was one of the last people to give Trent money before his house of cards collapsed. I also instinctively knew the money was gone forever. You don't hear stories about con artists having all the money stashed away in an account somewhere. Retaining a lawyer would also cost a significant amount. Why throw good money after bad? However, my friends wanted to pursue justice, so we filed a petition by the end of August.

I had to tell my wife what happened. We have an honest relationship . . . and I didn't want correspondence from a lawyer's office or the FBI to show up at our house unannounced. That would be awkward. Despite our financial security, it was an uncomfortable conversation. She trusts me to manage our family's finances and investments. I take those responsibilities and her financial peace of mind seriously, so it was a humbling moment.

We were fortunate. I have a high income and have made other solid investments, and I am financially independent before age 50. If we were not FI, my feelings of guilt, shame, and anger would have been amplified. I am in the privileged position of being able to consider it an expensive lesson; losing $75,000 to a con artist hurt my ego more than my net worth. However, not all victims of financial crimes are so lucky. Some have their retirement savings wiped out and must return to work, while others lose their home, requiring them to move in with family or worse. Financial crime victims have been found to have a higher incidence of depression and suicidal thoughts.

The Analysis: My 3 Mistakes

I made at least three mistakes that contributed to my being defrauded.

Transferring Trust

The term con men is short for confidence men, fraudsters who gain your trust before ripping you off. Affinity fraud is perpetrated by those with whom you have things in common: profession, hobbies, military service, religion, ethnicity, etc. Con artists often infiltrate tight-knit communities and get the other members to spread their investment ideas for them, inadvertently ensnaring their friends. Trent and I were about the same age. We were both medical professionals. We lived in the same city, and we were interested in growing medical businesses. He infiltrated my friend group and gained their confidence. My mistake was transferring trust; I trusted my friends because they had earned it, but Trent had not.

FOMO

The fear of missing out is insidiously powerful. I had passed on the investment once before—not because of the merits of the deal, but because I was preoccupied with other things at the time. I get a lot of investment opportunities, and I almost always say no. But I doubted myself when my friends started making money. A voice in the back of my head told me I was missing out. When I had a second chance to invest in an already "profitable" venture, I joined without hesitation, which led to my third and most egregious error.

Laziness

I didn't do any due diligence. None. Dr. Dahle was generous when he included "being busy" as a reason doctors get swindled. I was just lazy. While it is excusable that I didn't seek references since my friends were already investors, doing no other diligence is not. How long would it have taken to look up Trent's record with the state dental board, the secretary of state, and the Better Business Bureau? I would have quickly discovered that he voluntarily surrendered his Texas dental license in 2016 and that his owning a dental practice in the state wasn't even legal. It would have taken 20 minutes on Google to discover an arrest record for assaulting a girlfriend, dental board actions, and other suspicious news articles. Any of those items would have deterred me, but I didn't take the time. This mistake is the hardest to accept because I have always prided myself on being hard-working. In this case, I fell short.

More information here:

7 Tips to Avoid Investment Scams

The Consequences

Over the next 5 1/2 years, I would hear periodic updates about Trent from the other defrauded investors—something in the news, a Facebook post showing him in Costa Rica, or correspondence from an FBI agent. Otherwise, I forgot the whole thing and moved on with my life.

I never blamed Barry for what happened. There was no malice when he introduced me to Trent. He was just passing along an opportunity that had been passed to him. Unfortunately, this is how affinity fraud works. I alone am responsible for the decisions I make, and losing a long-time friend would just compound my mistakes. We are still great friends and business partners.

I received a letter from the US Department of Justice on October 26, 2023, reporting that Trent pled guilty and was convicted of one count of wire fraud. I was given the option to provide a written Victim Impact Statement: "In preparing your statement, you may want to think about how this crime has affected your life and made you feel." The judge considers these statements when determining the sentence. I didn't send the statement, but the letter inspired me to write this guest post.

A press release from the Department of Justice dated January 29, 2024, stated that "In addition to imposing the 36-month prison sentence, the court sentenced ****** to a supervised release term of three years and ordered him to pay $2,182,760.63 in restitution." I don't think that I will ever see a penny of the money I invested. Still, I am happy that the case is now closed. I feel bad for Trent. I know I shouldn't, but I do. I don't know when he jumped the shark from legitimate entrepreneur to fraudster, but by 2016, he was likely running a Ponzi scheme, paying out distributions from later investors. I genuinely can't understand why someone would work so hard to become a dentist and then throw it all away.

How to Protect Yourself

Before you invest, there are ways to protect yourself. Start with the basics: Don't be pressured into acting quickly, don't invest in anything you don't understand, beware of promised high returns or no-risk investments, and be wary of any investment that finds you. I have four additional action items to help keep you out of trouble.

#1 Educate Yourself About Investing and Finance

Doctor salary + Lack of financial education = Target for criminals.

You can remove one variable from this equation by educating yourself. If you're reading The White Coat Investor, you are already on the right path. But don't get overconfident, even if you read every book and blog. Have you ever seen someone who knew just enough karate to get themselves beat up? That was me. Today's financial fraudsters can be quite sophisticated with complicated digital financial crimes being common. And don't underestimate the persuasive power of a good old-fashioned con artist.

#2 Perform Due Diligence

This one should be obvious, but sometimes, the easiest things are what we forget. I did. No matter how much you like or trust someone and no matter how charming they are or who else is investing with them, look them up before you give them money. Perform a Google search and online background check, scour their social media pages, and verify any professional certifications or degrees. If they are a financial professional, visit websites like BrokerCheck to confirm credentials and check for complaints. Ask for references and actually call them. Review financial documents and projections to ensure they make sense. Trust your instincts and refrain from investing if you find anything irregular during due diligence. Where there is smoke, there is fire.

#3 Seek Advice

Before you invest with anyone, talk to the people in your life about it. Discuss with your spouse, best friend, accountant, lawyer, or financial advisor (fee-only, of course). Not everyone is the visionary you are, and perhaps they can't see what you do in the investment. But visionaries sometimes hallucinate, so it's good to have another set of eyes to advise you. You don't always have to follow their advice, but you'll rarely regret the second opinion.

#4 Diversify Your Investments

I walked away from this fiasco relatively unscathed because I didn't invest a substantial portion of my net worth. I invest in securities, real estate, and private businesses. I also diversify within those asset classes, using broad-based index funds, commercial and residential real estate in different cities, and multiple private company investments. If your investments are too highly concentrated, the impact of fraud is magnified along with your losses. I even diversify between brokerages, with my securities split between accounts at Vanguard and E-Trade. My real estate holdings are within a Texas Series LLC, and I only keep cash up to the FDIC-insured limit at each bank. This may be overkill, but broad diversification can keep you from being totally wiped out by a bad decision or fraud.

#5 Other Resources

Here's a list of websites that can further help.

- https://www.investor.gov

- https://brokercheck.finra.org

- https://www.sec.gov/enforce/public-alerts

- https://www.sec.gov/litigations/sec-action-look-up

The Bottom Line

Anyone can become a victim of financial fraud, regardless of income or profession. Your high salary as a medical professional makes you an especially appealing target. While gaining a financial education is a critical step, it isn't enough to prevent fraud. For every Nigerian prince, there is a Bernie Madoff, former chairman of the SEC and (formerly) one of the most respected men on Wall Street. For every huckster peddling penny stock, there is a Sam Bankman-Fried, who briefly conned his way to a $26 billion net worth. A con artist can be your neighbor, colleague, church member, or dentist. There is a Trent in every state and every town, including yours.

The first step toward protecting yourself is knowing that investment fraud exists and acknowledging that it can happen to you. If you are suspicious of an investment opportunity or have been the victim of fraud, peruse the list of resources above. I encourage you to speak up against those who have committed financial crimes. It may be too late to recover your money, but you can protect others from becoming victims.

Have you ever been the victim of a financial scam? What happened? How else can people avoid con artists? Comment below!

[Editor's Note: Dr. Neill Slater practices emergency medicine, business, and family life in Texas and writes about his experiences at Business Is The Best Medicine. This article was submitted and approved according to our Guest Post Policy. We have no financial relationship.]The post How This Financially Literate Doctor Got Scammed Out of $75,000 appeared first on The White Coat Investor - Investing & Personal Finance for Doctors.

Be sure to Refinance Your Student Loans, sign-up for our Online Courses, and listen to the WCI Podcast!

Unsubscribe from these daily financial articles

Manage all your subscriptions

If you NEVER want ANY emails from us again, you can unsubscribe from EVERYTHING | Update your email address by clicking here

White Coat Investor | P.O. Box 520421, Salt Lake City, Utah 84152

No comments:

Post a Comment

Keep a civil tongue.